A Guide to Reading Massage Therapy Research

/As massage therapists, we’re often told we need to keep up with the latest research to make sure our practice is as evidence-based as possible. Unfortunately, many of us have very little experience in reading and evaluating research, so keeping up with the newest evidence can be intimidating. How do we know if a particular piece of research is good, and should be considered when we create our treatment plans?

“How do we know if a particular piece of research is good, and should be considered when we create our treatment plans?”

The Hierarchy of Evidence

Before we delve into the details of what makes a good study, it’s important to understand that scientific evidence forms a hierarchy. The higher up the hierarchy, the better the quality of the evidence. Although there are some variations on the hierarchy, some including more levels than others, the order is always the same. The most common levels include, from top to bottom:

Systematic Reviews compare many studies on the same topic and evaluate them to see if the conclusions about the topic are consistent.

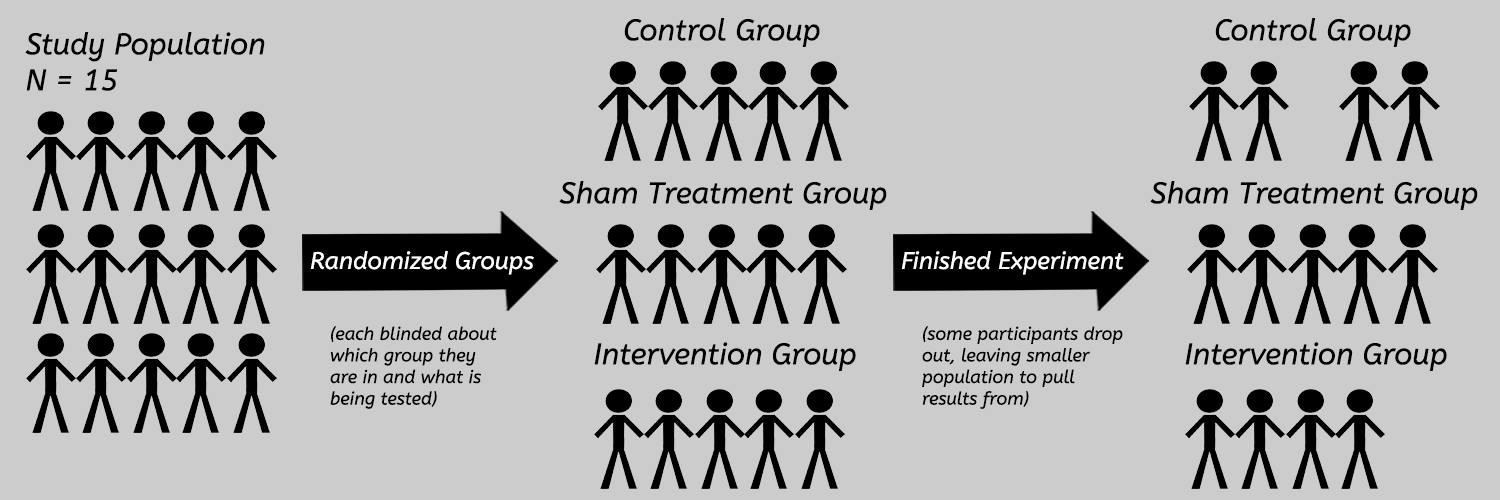

Randomized-Controlled Trials (RCTs) are what we encounter often in published massage therapy research. They are experimental studies where one group is exposed to an intervention (like massage), and another group is exposed to a placebo (sham) treatment, no treatment at all, or sometimes both if there are enough participants for three groups. The participants should be randomized (placed randomly) into those groups, in order to minimize the chances of factors other than the massage treatment influencing the outcome of the study.

Case Control Studies and Cohort Studies are types of observational studies. In these types of studies, experimenters don’t try to control who is or isn’t exposed to the intervention (like in an RCT); they just observe the effect of the intervention on a group of people. In cohort studies, the ‘cohort’ is a group of people who have some common link (like all being born around the same time, or of a particular race), whereas in case control studies participants are chosen because they have a common health problem.

Case Series and Case Reports are descriptions of a particular patient’s experience with a health problem – their symptoms, how it’s impacting their lives, their daily routines, what treatments they received, their responses to those treatment(s), and so on. Case reports involve a single patient, case series involve multiple patients, and neither involves controls or randomization. Case studies and case reports can provide important information, but they cannot demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship between the massage treatment and the outcome.

The Hierarchy of Evidence

Anecdotes are personal experiences a patient describes regarding a particular treatment. They are highly subjective, and often don’t include any information aside from the benefit they believe they experienced from the treatment.

Animal Studies are experiments completed on animals. Their purpose, in health care, is to gather preliminary information about the effect of an intervention, and how it might impact human patients. However, results from animal studies are often exaggerated to support claims that haven’t been properly demonstrated in humans.

This article focuses mostly on RCTs, since they’re the most common type of published massage therapy research accessible to most of us, and they are fairly high up the evidence hierarchy. However, not all RCTs (or experimental studies) are designed equally. Being higher up on the hierarchy is good, but it’s not a guarantee that a particular piece of research is well designed.

“Being higher up on the hierarchy is good, but it’s not a guarantee that a particular piece of research is well designed.”

What to Look for When Reading a Research Study

First of all, it’s important to have access to the full text of a research study in order to evaluate it. It’s really common to find only the abstract of a study, which is just a summary written by the author. It doesn’t include all the information you’ll need to assess the study’s quality.

TIP: IF YOU FIND AN ABSTRACT THAT REALLY INTERESTS YOU, USE GOOGLE SCHOLAR TO SEARCH FOR THE TITLE OF THE PAPER FOLLOWED BY “PDF”. OFTEN YOU’LL BE ABLE TO FIND A LINK TO A PDF VERSION FULL TEXT OF THE PAPER YOU CAN DOWNLOAD.

Once you have the full text of the paper, you can check for the following items as you’re reading it. Keep in mind that even the best papers are rarely perfect. A single – or even a couple of – lacking item(s) doesn’t necessarily make the paper bad. It’s the sum of all the items that help determine a study’s quality. It’s also important to note is that this list is not exhaustive, it’s just a place to get started if you’re new to reading research.

- Who are the authors?

Authors who are also practitioners are at a higher risk for bias than neutral authors. There may also be conflicts of interest if the authors of a paper stand to financially benefit from the results. Where the authors are located is something else to check – some countries are more suspect for bias on various topics (like acupuncture) than others, for political reasons. Checking to see if the authors have other published can help establish their credibility as well.

- Which journal published this study?

Where a study is published can provide some hints about its quality. Some journals have very rigorous quality assurance practices, including credible peer review, but others basically just cash your cheque and publish anything you send. A journal’s impact factor is the number of citations a journal gets relative to the number of articles the journal publishes in a given period of time, and it can be a good indicator of how many other journals use it as a reference. You can use the Scientific Journal Rankings tool to browse journal rankings for free, or check out to Beall’s List of Predatory Publishers to see if the journal is one to be avoided for sketchy practices.

- What question is being studied (what is the hypothesis) in this piece of research?

What the authors are actually studying in the paper is important. Sometimes, the authors’ hypothesis contains assumptions that might not be scientifically supported. For instance, a hypothesis like “How large is the effect of Reiki on cancer?” relies on the assumption that Reiki energy exists. If the hypothesis relies on unsupported assumptions, it’s definitely a bad sign. Science always assumes that a relationship between two variables (like “Reiki” and “cancer”) is not demonstrated to exist until enough evidence shows otherwise. If a hypothesis assumes that a previously undemonstrated novel relationship exists already, that’s a definite red flag.

- What is the study’s population?

The population of a study refers to the participants. The “N-value” of a study is the population; “N=47” means there were 47 people. Generally speaking, larger populations are better at consistently demonstrating real effects. Check to see how many participants actually made it all the way through the experiment, because it can sometimes be very different from the number that started. The selection (inclusion and exclusion) criteria refers to how participants were selected to participate in the study. Depending on what is being studied, certain demographics (age, gender, race, level of activity, etc.) might be included or excluded from the study. Be wary of studies which have very narrow inclusion criteria or a very small population, but talk about their results as though they are applicable to the general public.

Randomized-Controlled Trials (RCTs)

- What controls are in place for the study?

Controls refer to the processes the authors set up to (hopefully) prevent outside forces from influencing the results. Some of the important controls to look for are a control group and a sham treatment group. A control group is a group within the study’s population that isn’t receiving the intervention, while the sham treatment group receives a fake treatment or a placebo. If the study doesn’t include controls, there’s no way to tell if any results were due to the treatments, or something else (time, laying down for the same time, placebo, etc.).

- Were the treatments standardized?

The authors should make sure that each participant (except for those in the control and sham groups) received the same intervention in the same way. A good study will describe, in detail, how each treatment was applied, and how the treatments were standardized. The description should be detailed enough for another practitioner to reproduce the treatment almost exactly. Being able to reproduce results is important for future studies.

- Was there any blinding?

To help reduce bias as much as possible, study authors should the limit how much the participants and therapists applying the intervention and measuring the raw results know about what the study is examining. This process is referred to as ‘blinding’. If the participants and therapists know what the authors are looking for, they might alter their responses or what they are doing (either consciously or subconsciously), which can skew the results. ‘Single-blinded’ means the participants were blinded, and ‘double-blinded’ means both the participants and the therapists were blinded.

- What was actually being measured?

The study’s hypothesis might be something that can’t be directly measured objectively. For example, the hypothesis might have something to do with pain or stress, and there isn’t a way to directly measure those things objectively with any degree of accuracy. The study design sometimes relies on indirect measurements, like measuring cortisol levels as a measure of stress. The problem with using indirect measurements is that, with complex, multi-faceted issues like pain and stress, the indirect measures aren’t always reliable enough to establish a clear answer. We can say, for instance, whether cortisol levels were changed in a study, but we can’t guarantee that a change in perceived stress was experiences by the participants. Unfortunately, this is a common weakness in a lot of massage therapy research.

- How were measurements taken?

The equipment and protocols used to capture raw results can impact the credibility of a study. Good studies will describe, in detail, how measurements were recorded, and will strive to use the most accurate equipment and protocols possible. Outdated or inappropriate measuring tools will give inaccurate results, which undermine the rest of the study. If you’re not familiar with the measuring methods described in a study, research them a little to see if they were a good fit for the study. Be wary of studies that rely only on questionnaires and other subjective tools, since it’s hard to get accurate, objective results that way.

- Do the results support the conclusion?

The results section is probably the most intimidating part of a research study. There usually a lot of statistics and charts, which can be very confusing at first. I would highly recommend you don’t just skip this section though. Even if you don’t understand 100% of the statistics, there’s a couple items which aren’t too hard to decipher.

You’ll probably see some P-values (ex: “p=0.05”). P-values relate to a scientific premise called the null hypothesis, but it might be helpful for beginners to think of them as describing likelihood of the result happening even if the intervention didn’t actually influence the outcome. A P value of 0.05 or lower for a result is usually a good sign (0.01 is even better), anything higher than 0.05 makes the result a bit suspect.

Results are usually shown as mean (average) values, and there should be something called a standard deviation for each result. The standard deviation is a description of how “close” most of the results were to the mean. A small standard deviation (in comparison to the mean) for a measured variable means the measurements for that variable were all very similar across the group.

If the authors conclude their study supports a particular claim, but their results aren’t very definitive, they might be exaggerating the findings.

- Are the results clinically significant, or just statistically significant?

A result that is statistically relevant doesn’t necessarily mean it’s useful in practice. For instance, a result might represent an effect that is large enough to show up in the experiment, but not large enough to be noticeable by our clients in the clinic. Or, the effect might be quite large, but in a way that may harm our clients or exacerbate their symptoms.

- Do the results conflict with mainstream science?

Scientific progress is almost always made in baby steps, not in giant leaps that overturn decades of credible evidence. If the results of a study seem to conflict with well-established and well-supported principles of chemistry, biology, physics, and other sciences, the results should be treated with a huge degree of skepticism. As the science educator Carl Sagan says, “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”.

- Have the results been replicated by other studies?

If the study’s results have been replicated by other studies (by different authors), it improves the study’s credibility. However, you’ll want to evaluate those studies for strengths and weaknesses too. Several poorly designed studies with similar results aren’t as credible as a singular study with a more rigorous design. Quality takes precedence over quantity.

- Are limitations mentioned and addressed?

Even the best-designed studies have some limitations. It might have been access to the most accurate equipment; a lack of standardization, controls, or blinding; a small population; or one of hundreds of other items which could have been improved to make the study more robust. A good study will acknowledge any glaring limitations, discuss how the authors tried to accommodate for them, and provide guidance for how they might be addressed in future studies.

- Do the references in the article support the claims the authors are making?

All credible research papers will include references to other studies which the authors use to support their position, and reinforce any claims they make throughout the study. The list of references is usually found at the end of the paper. However, sometimes weaker studies will use references that don’t actually support their position – don’t take the author’s word for it. Take the time to look into the studies that the authors reference to see if those studies are strong, credible, and actually do support whatever claim the author says they do. Apply the same steps you just did to the current study to the reference studies to check for their relative strengths and weaknesses.

Now that we’ve addresses several potential strengths and weaknesses to look for, it’s worth saying again: a single weakness is rarely enough to determine that a study isn’t well designed. There are exceptions of course, but a single (even a couple of) weakness(es) will not usually undermine an entire study – it’s the sum of all the studies strengths and weaknesses that should be considered.

“Keep in mind that even the best papers are rarely perfect. A single – or even a couple of – lacking item(s) doesn’t necessarily make the paper bad. It’s the sum of all the items that help determine a study’s quality. It’s also important to note is that this list is not exhaustive, it’s just a place to get started if you’re new to reading research.”

Practice Makes Perfect

Reading and interpreting the relative strength of research papers is not a skill you develop overnight. It takes a good deal of practice, so don’t be discouraged if you “miss” something in a paper, or a paper you originally thought was great turns out to be a bit less well-designed than you initially thought.

A single poor study, even a single well-designed study, is rarely enough on its own to ‘close the book’ on a healthcare question or topic. Remember that evidence-based practice evaluates all the evidence on a particular topic, and the truth is that a lot of questions are still unanswered. A number of well-designed studies that all show the same results and conclusions are a lot more convincing than a couple of poorly designed studies which show different results. If you find a study or piece of research that really interests you, make a point of looking up other papers on the same topic to see if the results are reproduced, and apply your critical thinking skills to those papers as well!

Continuing Down The Rabbit-Hole: You can usually find some support in evaluating a particular study on the Skeptical Massage Therapists group. It’s an international group for massage therapists to skeptically evaluate research, claims made in various manual therapy professions, and other related topics of interest to massage therapists who are also scientific skeptics. Be prepared to back up any claims you make with credible research!

Bryan Quesnelle

Massage Therapist and Web Developer at ClinicWise

I lead a double life as a registered massage therapist and a web developer in Kitchener, Ontario. When I'm not treating patients or developing products for ClinicWise, I'm usually building websites for other businesses and organizations.

Reproduced with permission from ClinicWise